The Easiest Person to Fool 2 Hierarchy of Disagreement

"The first principle is that you must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool."

- from lecture "What is and What Should be the Role of Scientific Culture in Modern Society", given at the Galileo Symposium in Italy (1964) Richard Feynman American theoretical physicist

"The first principle is that you must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool."

- from lecture "What is and What Should be the Role of Scientific Culture in Modern Society", given at the Galileo Symposium in Italy (1964) Richard Feynman American theoretical physicist

“There are two ways to be fooled. One is to believe what isn't true; the other is to refuse to believe what is true.”

―

Psychologist Nicole Currivan

She was quoted in an article entitled The Neuroscience of How Personal Attacks Shut Down Critical Thinking. I will use some excerpts.

"First we need to know a bit about two regions of the brain that are fairly at odds with one another.

The prefontal cortex, which…is in the front of the brain if you’re facing forward. And the limbic system, which… is a huge chunk of many regions in the center of the brain. The pre-fontal cortex is our executive function. It helps us plan and decide what actions best meet our needs and is responsible for social inhibition, personality, and processing new information. It’s the part that says “you could have garlic bread tonight but you also don’t want to sit alone in the corner”.

The limbic system…is responsible for emotions and formation of memory. It reminds you that you love garlic bread and you were really embarrassed, too, the last time you ate it and no one sat next to you. So the important point about these two areas is: activation of one region generally results in deactivation or inhibition of the other, so they have an inverse relationship. This is because in situations of low or moderate stress, the prefontal cortex inhibits the amygdala. The amygdala is responsible for emotions that relate to the four 4’s: fight, flight, feeding–and mating…

So it makes us feel things like fear, reward, and anger that normally the prefrontal cortex can respond to with a spot of reason and inhibition. In a normal, low stress situation, you want the garlic bread or the cookie, for example, but you can decide whether or not to eat it because your prefrontal cortex is still engaged. And as your stress level may increase it gets harder to make those choices. Your rational thought capacity is there less and less and less to police your emotions when stress increases.

And this is where things can get ugly. If something extremely stressful happens that lights up the amygdala, it has the power to shut down the prefrontal cortex completely. It has this fight or flight or freeze response…and it’s instantaneous. It’s something that evolved for situations in which there is no time for decision making. You can’t think about whether you want garlic bread, you have to drop it and run when you’re confronted with a tiger. And that’s incidentally why people don’t eat when they are stressed, and a lot of other things that happen to our body as part of the stress response.

So there are times, high stress times, when executive decision making processes go completely down to the count and our emotions take over. By threatening somebody, whether it’s real or perceived, you can completely disable people’s their ability to think straight. And this isn’t all or nothing, it’s on a continuum. A threat can be anything that causes stress from the tiger to just an uncomfortable thought. The level of stress will influence the amount of rational thought vs. emotion that’s available and it’s totally subjective to the perceived experience of stress.

And, adding to that, increased stress and emotion can influence memory. More emotion leads to stronger memories. And those memories last longer, especially if it’s a negative emotion. We all remember where we were the morning of 9/11. Last Tuesday? Not so much. And it makes sense that our brains do this since emotions fear and anger are about events we really want to be prepared for in case they happen again. At this point you’ve probably figured out that if your goal is to get someone to process new information and think critically about stereotypes (like [that] atheists are criminals or they should die) the absolute last thing we want is for them to feel threatened or attacked. The worst part about this is if you combine the process I just described with the sorts of negative emotional responses triggered by stereotypes and other biases, you can see that someone, if they’re all stressed by their perception of you…you’ve lost them, they’re not going to be able to listen. And you’ve additionally probably just given them a fun bad new memory to hang onto. "

"First, as fun as some of you may think it is to attack and argue and ridicule people, just be aware that that will legitimately slam the door to rational understanding–of any point you have. And if you can’t call the discussion you’re having calm and rational, you are in serious danger of indulging your own emotional satisfaction to the point where you’re reinforcing someone’s distrust in all of us. And starting with the premise that someone needs to change or the inherent assumption that “I know more than you” will definitely create a strong stress response and pushback as well. Something we all inherently know but we do it anyway.

Second, if you want to reduce stigma, it’s essential to reduce limbic system activation as much as possible whenever you’re talking to somebody. Any kind of threat, real or perceived, in the current moment or even just something they remember, something bad that they remember about the stigma that’s on the person they’re talking with, can shut down their ability to take in new information. And shuts down possibility for change. So fear is really the enemy of trust in this case and it’s mistrust that the studies have found people have for atheists.

Third, if you want to change people’s opinion of you, making the conversation rewarding for them will definitely increase the likelihood that will happen. The less stressed they are, the more their brain will receive and process new information.

Fourth, I haven’t even begun to scratch the surface here with applicable brain science, but consider that emotions are highly contagious. And, unfortunately, negative emotions are more contagious than positive ones. So your stress will definitely spread throughout a room. And it also doesn’t work to hide your stress from people because it actually makes their blood pressure go up if you try. So don’t try to change people’s thinking about you if you’re stressed or in a bad mood, just wait until you can be calm and pleasant so it can be rewarding for everybody. " end quote. Nicole Currivan psychologist

I could try to dig up lots of articles on the brain and limbic system and amygdala and executive function but the hypothesis that is currently accepted (like any hypothesis it could be falsified in the future) is that when our limbic system and amygdala are triggered we have our critical thinking impaired. We do poor at thinking when we are swept up in strong emotions and in particular fear, anger and as Jon Atack pointed out to me disgust.

Anyone very interested in this can read the simple introductory book The Brain by David Eagleman or the absolutely brilliant Subliminal by Leonard Mlodinow or the truly challenging in-depth analysis of Behave by Robert Sapolsky.

I wrote a long post on Subliminal at Mockingbird's Nest blog on Scientology and want to just point out a few things that correspond to with points Nicole Currivan made.

In chapter 7 (Sorting People and Things) of his book Subliminal, Leonard Mlodinow took on the human tendency to place people and things in categories. He started with the example of a list of twenty groceries being difficult to remember just from hearing them said aloud. But if they are sorted into categories like vegetables, cereals, meats, snacks etc then it's easier to remember them.

Mlodinow wrote, "categorization is a strategy our brains use to more efficiently store information." (Page 145)

"Every object and person we encounter in the world is unique, but we wouldn't function very well if we perceived them that way. We don't have the time or the mental bandwidth to observe and consider each detail of every item in our environment." (Page 146)

Mlodinow wrote, "If we conclude that a certain set of objects belongs to one group and a second set of objects to another, we may then perceive those in different groups as less similar than they really are. Merely placing objects in groups can affect our judgment of those objects. So while categorization is a natural and crucial shortcut, like our brain's other survival-oriented tricks, it has its drawbacks." (Page 147)

Mlodinow described an experiment in which people were asked to judge the length of lines. Researchers put several lines in a group A and others in a group B. Researchers found people thought lines that are in a group together are closer in length than they actually are and the difference in length between lines from different groups is different than it really is. Similar experiments with color differences and groups and guessing temperature changes in a thirty day period within one month or from the middle of a month to the middle of the next month is seen as more extreme. Same number of days but just saying it's a different month increases the estimate of change.

The implications are stunning. If people can be placed in categories and thought of as fundamentally defined by those categories we easily can misjudge people.

This reminds me of a terrible quote:

“The leader of genius must have the ability to make different opponents appear as if they belonged to one category. ” ―Adolf Hitler

That's a reminder of a terrible problem with human behavior and categorization.

Mlodinow wrote, "In all these examples, when we categorize, we polarize. Things that for one arbitrary reason or another are identified as belonging to the same category seem more similar to each other than they really are, while those in different categories seem more different than they really are. The unconscious mind transforms fuzzy differences and subtle nuances into clear-cut distinctions. Its goal is to erase irrelevant detail while maintaining information on what is important. When that's done successfully, we simplify our environment and make it easier and faster to navigate. When it's done inappropriately, we distort our perceptions, sometimes with results harmful to ourselves and others. That's especially true when our tendency to categorize affects our view of other humans--when we view the doctors in a given practice, the attorneys in a given law firm, the fans of a certain sports team, or the people in a given race or ethnic group as more alike than they really are." (Page 148)

Mlodinow wrote on how the term "stereotype" was created by French printer Firmin Didot in 1794. It was a printing process that created duplicate plates for printing. With these plates mass production via printing was possible.

It got its modern use by Walter Lippmann in his 1922 book Public Opinion. Lippmann is perhaps best known nowadays as a person frequently quoted by noted intellectual and American dissident Noam Chomsky. Chomsky has criticized the use of propaganda to manage populations by the government, wealthy individuals, corporations and media.

From Subliminal Mlodinow quoted Lippmann, "The real environment is altogether too big, too complex, and too fleeting for direct acquaintance...And although we have to act in that environment, we have to reconstruct it on a simpler model before we can manage with it." (Page 149) Lippmann called that model stereotype.

Lippmann in Mlodinow's estimation correctly recognized the source of stereotypes as cultural exposure. In his time newspapers, magazines and the new medium of film communicated in simplified characters and easily understood concepts for audiences. Lippmann noted stock characters were used to be easily understood and character actors were recruited to fill stereotypes.

Mlodinow wrote, "In each of these cases our subliminal minds take incomplete data, use context or other cues to complete the picture, make educated guesses, and produce a result that is sometimes accurate, sometimes not, but always convincing. Our minds also fill in the blanks when we judge people, and a person's category membership is part of the data we use to do that." (Page 152)

Mlodinow described how psychologist Henri Tajfel was behind the realization that perceptual biases of categorization lie at the root of prejudice. Tajfel was behind the line length studies that support his hypothesis. Tajfel was a Polish Jew captured in France in World War II. He knew a Frenchman would be treated as an enemy by the Nazis while a French Jew would be treated as an animal and a Polish Jew would be killed.

He knew how he would be treated was entirely limited by the category he was placed in. Being a Polish Jew was a guarantee of death and so he impersonated a French Jew and was liberated in 1945. Mlodinow wrote, "According to the psychologist William Peter Robinson, today's theoretical understanding of those subjects "can almost without exception be traced back to Tajfel's theorizing and direct research intervention." (Page 153)

Mlodinow wrote, "The challenge is not how to stop categorizing but how to become aware of when we do it in ways that prevent us from being able to see individual people for who they really are." (Page 157) contrast this with

"At this point you’ve probably figured out that if your goal is to get someone to process new information and think critically about stereotypes (like [that] atheists are criminals or they should die) the absolute last thing we want is for them to feel threatened or attacked. The worst part about this is if you combine the process I just described with the sorts of negative emotional responses triggered by stereotypes and other biases, you can see that someone, if they’re all stressed by their perception of you…you’ve lost them, they’re not going to be able to listen. And you’ve additionally probably just given them a fun bad new memory to hang onto. " Nicole Currivan

Mlodinow wrote, "The stronger the threat to feeling good about yourself, it seems, the greater the tendency to view reality through a distortion lens."

(Page 197) compare to "First, as fun as some of you may think it is to attack and argue and ridicule people, just be aware that that will legitimately slam the door to rational understanding–of any point you have. And if you can’t call the discussion you’re having calm and rational, you are in serious danger of indulging your own emotional satisfaction to the point where you’re reinforcing someone’s distrust in all of us. And starting with the premise that someone needs to change or the inherent assumption that “I know more than you” will definitely create a strong stress response and pushback as well. Something we all inherently know but we do it anyway." Nicole Currivan

"Second, if you want to reduce stigma, it’s essential to reduce limbic system activation as much as possible whenever you’re talking to somebody. Any kind of threat, real or perceived, in the current moment or even just something they remember, something bad that they remember about the stigma that’s on the person they’re talking with, can shut down their ability to take in new information. And shuts down possibility for change. " Nicole Currivan

"As the psychologist Jonathan Haidt put it, there are two ways to get at the truth: the way of the scientist and the way of the lawyer. Scientists gather evidence, look for regularities, form theories explaining their observations, and test them. Attorneys begin with a conclusion they want to convince others of and then seek evidence that supports it, while also attempting to discredit evidence that doesn't. The human mind is designed to be both a scientist and an attorney, both a conscious seeker of objective truth and an unconscious, impassioned advocate for what we want to believe. Together these approaches vie to create our worldview." (Page 200)

Mlodinow went on, "As it turns out, the brain is a decent scientist but an absolutely outstanding lawyer. The result is that in the struggle to fashion a coherent, convincing view of ourselves and the rest of the world, it is the impassioned advocate that usually wins over the truth seeker." (Page 201)

Mlodinow described how we combine parts of perception and filling in blanks with self approving illusions. We give ourselves the benefit of the doubt unconsciously and do it over and over in hundreds of tiny ways without conscious awareness. Then, our conscious mind innocently looks at the distorted final product and sees a seemingly perfect, consistent and logical representation of reality as memories with no clue it's not anything but a pure recording of the past.

Mlodinow described how psychologists call this kind of thought "motivated reasoning." He explained how the way we easily get this is due to ambiguity. Lots of things that we sense aren't perfectly and absolutely clear. We can acknowledge some degree of reality but somewhat reasonably see unclear things in ways that give ourselves every benefit of the doubt. We can do it for allies, particularly in comparison to our enemies. We can see in-group members as good, if it's unclear and out-group members as bad if it's unclear. We can set standards extremely high to accept negative evidence against ourselves and our groups or set standards extremely low to accept negative evidence against out-groups. We can act reasonable about it, but really are using how we feel about beliefs to determine our acceptance of those beliefs, substituting comfort with acceptance for proof being established.

Mlodinow described how ambiguity helps us to understand stereotypes for people we don't know well and be overly positive in looking at ourselves. He described studies and experiments that strongly support the idea we are incorporating bias in our decisions unknowingly.

Crucially Mlodinow added, "Because motivated reasoning is unconscious, people's claims that they are unaffected by bias or self-interest can be sincere, even as they make decisions that are in reality self-serving." (Page 205)

Mlodinow described how recent brain scans show our emotions are tied up in motivated reasoning. The parts of the brain that are active in emotional decisions are used when motivated reasoning occurs, and we can't in any easy way divorce ourselves from that human nature.

Numerous studies have shown we set impossibly high standards to disconfirm our beliefs, particularly deeply held emotional beliefs like religious and political beliefs. We set impossibly low standards for evidence to confirm our beliefs.

We also find fallacies or weaknesses in arguments, claims and sources of information we disagree with while dropping those standards if the information supports our positions. It's so natural we often don't see it in ourselves but sharply see it in people with opposite beliefs. They look biased and frankly dimwitted. But they aren't alone in this.

We see ourselves as being rational and forming conclusions based on patterns of evidence and sound reason, like scientists but really have more lawyer in us as we start with conclusions that favor us and our current beliefs, feelings, attitudes and behaviors and work to find a rational and coherent story to support it.

Mlodinow ended his book, "We choose the facts that we want to believe. We also choose our friends, lovers, and spouses not just because of the way we perceive them but because of the way they perceive us. Unlike phenomena in physics, in life, events can often obey one theory or another, and what actually happens can depend largely upon which theory we choose to believe. It is a gift of the human mind to be extraordinarily open to accepting the theory of ourselves that pushes us in the direction of survival, and even happiness." (Page 218) end quote

So, between our prejudices, unseen biases and tendency to shut down critical thinking is there any hope ? Crazy as it sounds, we might actually want to have interactions with other human beings that are more than insults and close minded exchanges of motivated reasoning.

In 2008 computer programmer Paul Graham wrote How To Disagree and I am going to quote an excerpt. I think it is a useful reference and starting point for many discussions. Scientology and other cults encourage poor critical thinking, lack of recognition of individual qualities of people and items within categories and emotionally charged reactions to information. We all at times can get sidetracked from addressing main or relevant points to go off on tangents.

So, a guideline as to what to stick with or try to follow to stay on topic or on point is useful. If several people read it, understand it, understand that using tactics that trigger being more emotional often impair good judgement, impair the ability to to see individual people and situations and circumstances as they are with many subtle differences and unique details, and impairs even the ability to receive information and remember it accurately.

If behavior that cults like Scientology encourage that lowers the level of thinking can be identified and avoided thus making debates and discussions more rational wouldn't that be a good thing ?

Now I personally think that name-calling, ad hominem attacks, tu quoque (meeting criticism with criticism), the genetic fallacy (addressing the genesis or source of a claim rather than the claim), appeal to authority (treating a source as so infallible that a claim they support is treated as proven by their support without examination), glittering generalities or hasty generalities or red herring fallacies should be discouraged.

As none of us are perfect they will pop up. When one does if someone tells me I SHOULD pause and consider the claim that I have used a fallacy. Sometimes I will recognize that and can restate a claim or withdraw it. This doesn't mean a claim by the other person "wins" or is proven true. Thinking your claim is proven by the use of a fallacy in a claim in opposition to yours is the fallacy fallacy. I didn't make that up.

If I say "the earth is flat" and you say "only an idiot would say that", you just used a fallacy in your claim but it is irrelevant to mine. By the way I believe in a roughly globe shaped earth. So, we can acknowledge the presence of a fallacy in a claim and not treat it as life threatening or world shattering. Just because someone uses a fallacy in a claim doesn't mean their overall concept is wrong, sometimes it is and sometimes it isn't. Additionally, sometimes a person will claim a fallacy is being used when it is not. You can point this out.

I have many times posted articles critical of Scientology, for example, and got insults in response. I have asked that the person address my claims and not use ad hominem attacks many times in response. Curiously, many times the people defending Scientology often tell me I am using ad hominem attacks and they are not. The great thing about the internet is you can re-read comments and SEE what is there.

Often I post something saying Scientology is a harmful fraud, for example. Someone responds "only an idiot who never actually did anything in Scientology would ever say that because they lack the spiritual awareness to even comprehend Scientology." Okay.

I respond by telling them I was in Scientology for twenty five years, so their claim is false. They respond "then you must have not REALLY done Scientology ! Because it ALWAYS works when done properly !"

So , they are saying "if Scientology gets the results you want it is genuine but if it fails it is something else", but they have married their claims to unproven assumptions about me. Those are what is helping to turn down and hold do their critical thinking. And that is the barrier to beneficial communication.

You can call me any insult you can think up, and people certainly have. Go ahead, knock yourself out. It doesn't make them true. Not even a little bit. It also doesn't leave you in great shape for thinking.

Scientology gets people to think and feel in extremes. Extreme hate, extreme arrogance, extreme condescension, extreme disgust. These are not useful for critical thinking.

For a Scientologist or Independent Scientologist who chooses to engage with people who criticize Scientology I have a question - why can't you respond to criticism without using fallacies ? And the mind reading of "knowing my thoughts and motives and beliefs" without evidence is a fallacy. Scientology encourages people to think that critics have certain beliefs and motives and feelings but without good evidence deciding that a critic or person who disagrees with you thinks or feels something is making an unfalsifiable claim. It cannot be tested, it cannot be proven or disproven. It is a red herring and waste of time. If you believe it then it is a way to accept stereotypes and see people who disagree as broad categories and to reduce your own critical thinking. It may be emotionally comforting but it is terrible for critical thinking. You shouldn't rely on an assumption of knowing what someone else thinks. It's just not good logic.

We all do it. Human nature includes estimating the beliefs, feelings and behavior of other people. A large part of our thinking is devoted to it. But it is not a scientific approach, it is instinctive, largely unconscious, influenced by biases and highly inaccurate. So it is best set aside for careful examination of ideas in discussion. Just because I guess you think such and such is irrelevant to our conversation, unless that is the actual topic.

I dug up all this stuff for Scientologists who are going to keep on defending Scientology and resorting to the fallacy laden tactics Ron Hubbard required in Scientology doctrine. Everyone who was in Scientology for a long time and is familiar with a few dozen fallacies can see that Hubbard required them and frequently used them himself. Scientology is packed with generalities both glittering and hasty, appeal to authority regarding Hubbard, the genetic fallacy regarding critics and on and on. Scientology is set up to get you to think in those fallacies so you can never escape it.

And by getting members to become so emotional when criticism is detected, or even possible, it is intended to make any evidence against Scientology irrelevant because there is no critical thinking engaged to receive let alone examine it. Thousands and thousands of people have collected good arguments and evidence against Scientology to present to loved ones in Scientology only for it to prove worthless because they had no receptive audience to talk to.

Remember motivated reasoning is largely unconscious. We don't know when we are doing it. We can know we are more likely to do it if we get in a mode of using personal attacks and other fallacies. We can try to discipline ourselves to avoid insults, deciding the feelings and thoughts of people, using stereotypes and getting sidetracked in conversation. If a person starts with a central point then we can try to stick with that, not pivot off based on out feelings. If someone brings up criticism of someone or something I like or support for example feeling uncomfortable then solving that by pivoting to criticism of them or something or someone else is poor critical thinking. If I say for example that Ron Hubbard was convicted of fraud in France and you say a different court case with different people decades later was overturned that is completely irrelevant and we should both know it.

Everyone is free to behave however they choose. Plenty of people are going to insult you if you say much at all. Plenty will make up their unwarranted conclusions about your behavior, thoughts and feelings. That is life. It doesn't mean they are right. If they say it over and over and write it over and over it doesn't make it true.

If you want to have the opportunities to use your most logical, most rational thinking I recommend you remember that what they are doing is lowering their own rationality. They are diminishing their own thought. I can't pretend anyone can magically transform into a Vulcan like Spock and instantly become a perfectly logical being. That is not the point at all.

The point is we all can try to consider these ideas and if we believe it is likely true that resorting to personal attacks and similar measures reduces or shuts down critical thinking then we can strive to identify in ourselves when we do them and try to reduce it.

One last thing about critical thinking. Occasionally I see someone attack myself or Chris Shelton because we recommend critical thinking and write about it. It is not a magical transformation or religious practice. It is an approach to thinking in which you seek to improve the quality of your thinking. That is it. It doesn't mean you have achieved an enlightened state or higher awareness. It is just making an effort to fuck up less regarding thinking. So, if you can find any errors or flaws in the thinking, beliefs or conduct of someone who encourages critical thinking and you think " Aha ! I caught you ! You are not perfect ! So I can criticize you any way I want because you are a liar and a hypocrite !" You have missed the whole point of critical thinking. It is recognizing our flawed nature and trying to succeed despite it, not pretending to have overcome it.

―

Psychologist Nicole Currivan

She was quoted in an article entitled The Neuroscience of How Personal Attacks Shut Down Critical Thinking. I will use some excerpts.

"First we need to know a bit about two regions of the brain that are fairly at odds with one another.

The prefontal cortex, which…is in the front of the brain if you’re facing forward. And the limbic system, which… is a huge chunk of many regions in the center of the brain. The pre-fontal cortex is our executive function. It helps us plan and decide what actions best meet our needs and is responsible for social inhibition, personality, and processing new information. It’s the part that says “you could have garlic bread tonight but you also don’t want to sit alone in the corner”.

The limbic system…is responsible for emotions and formation of memory. It reminds you that you love garlic bread and you were really embarrassed, too, the last time you ate it and no one sat next to you. So the important point about these two areas is: activation of one region generally results in deactivation or inhibition of the other, so they have an inverse relationship. This is because in situations of low or moderate stress, the prefontal cortex inhibits the amygdala. The amygdala is responsible for emotions that relate to the four 4’s: fight, flight, feeding–and mating…

So it makes us feel things like fear, reward, and anger that normally the prefrontal cortex can respond to with a spot of reason and inhibition. In a normal, low stress situation, you want the garlic bread or the cookie, for example, but you can decide whether or not to eat it because your prefrontal cortex is still engaged. And as your stress level may increase it gets harder to make those choices. Your rational thought capacity is there less and less and less to police your emotions when stress increases.

And this is where things can get ugly. If something extremely stressful happens that lights up the amygdala, it has the power to shut down the prefrontal cortex completely. It has this fight or flight or freeze response…and it’s instantaneous. It’s something that evolved for situations in which there is no time for decision making. You can’t think about whether you want garlic bread, you have to drop it and run when you’re confronted with a tiger. And that’s incidentally why people don’t eat when they are stressed, and a lot of other things that happen to our body as part of the stress response.

So there are times, high stress times, when executive decision making processes go completely down to the count and our emotions take over. By threatening somebody, whether it’s real or perceived, you can completely disable people’s their ability to think straight. And this isn’t all or nothing, it’s on a continuum. A threat can be anything that causes stress from the tiger to just an uncomfortable thought. The level of stress will influence the amount of rational thought vs. emotion that’s available and it’s totally subjective to the perceived experience of stress.

And, adding to that, increased stress and emotion can influence memory. More emotion leads to stronger memories. And those memories last longer, especially if it’s a negative emotion. We all remember where we were the morning of 9/11. Last Tuesday? Not so much. And it makes sense that our brains do this since emotions fear and anger are about events we really want to be prepared for in case they happen again. At this point you’ve probably figured out that if your goal is to get someone to process new information and think critically about stereotypes (like [that] atheists are criminals or they should die) the absolute last thing we want is for them to feel threatened or attacked. The worst part about this is if you combine the process I just described with the sorts of negative emotional responses triggered by stereotypes and other biases, you can see that someone, if they’re all stressed by their perception of you…you’ve lost them, they’re not going to be able to listen. And you’ve additionally probably just given them a fun bad new memory to hang onto. "

"First, as fun as some of you may think it is to attack and argue and ridicule people, just be aware that that will legitimately slam the door to rational understanding–of any point you have. And if you can’t call the discussion you’re having calm and rational, you are in serious danger of indulging your own emotional satisfaction to the point where you’re reinforcing someone’s distrust in all of us. And starting with the premise that someone needs to change or the inherent assumption that “I know more than you” will definitely create a strong stress response and pushback as well. Something we all inherently know but we do it anyway.

Second, if you want to reduce stigma, it’s essential to reduce limbic system activation as much as possible whenever you’re talking to somebody. Any kind of threat, real or perceived, in the current moment or even just something they remember, something bad that they remember about the stigma that’s on the person they’re talking with, can shut down their ability to take in new information. And shuts down possibility for change. So fear is really the enemy of trust in this case and it’s mistrust that the studies have found people have for atheists.

Third, if you want to change people’s opinion of you, making the conversation rewarding for them will definitely increase the likelihood that will happen. The less stressed they are, the more their brain will receive and process new information.

Fourth, I haven’t even begun to scratch the surface here with applicable brain science, but consider that emotions are highly contagious. And, unfortunately, negative emotions are more contagious than positive ones. So your stress will definitely spread throughout a room. And it also doesn’t work to hide your stress from people because it actually makes their blood pressure go up if you try. So don’t try to change people’s thinking about you if you’re stressed or in a bad mood, just wait until you can be calm and pleasant so it can be rewarding for everybody. " end quote. Nicole Currivan psychologist

I could try to dig up lots of articles on the brain and limbic system and amygdala and executive function but the hypothesis that is currently accepted (like any hypothesis it could be falsified in the future) is that when our limbic system and amygdala are triggered we have our critical thinking impaired. We do poor at thinking when we are swept up in strong emotions and in particular fear, anger and as Jon Atack pointed out to me disgust.

Anyone very interested in this can read the simple introductory book The Brain by David Eagleman or the absolutely brilliant Subliminal by Leonard Mlodinow or the truly challenging in-depth analysis of Behave by Robert Sapolsky.

I wrote a long post on Subliminal at Mockingbird's Nest blog on Scientology and want to just point out a few things that correspond to with points Nicole Currivan made.

In chapter 7 (Sorting People and Things) of his book Subliminal, Leonard Mlodinow took on the human tendency to place people and things in categories. He started with the example of a list of twenty groceries being difficult to remember just from hearing them said aloud. But if they are sorted into categories like vegetables, cereals, meats, snacks etc then it's easier to remember them.

Mlodinow wrote, "categorization is a strategy our brains use to more efficiently store information." (Page 145)

"Every object and person we encounter in the world is unique, but we wouldn't function very well if we perceived them that way. We don't have the time or the mental bandwidth to observe and consider each detail of every item in our environment." (Page 146)

Mlodinow wrote, "categorization is a strategy our brains use to more efficiently store information." (Page 145)

"Every object and person we encounter in the world is unique, but we wouldn't function very well if we perceived them that way. We don't have the time or the mental bandwidth to observe and consider each detail of every item in our environment." (Page 146)

Mlodinow wrote, "If we conclude that a certain set of objects belongs to one group and a second set of objects to another, we may then perceive those in different groups as less similar than they really are. Merely placing objects in groups can affect our judgment of those objects. So while categorization is a natural and crucial shortcut, like our brain's other survival-oriented tricks, it has its drawbacks." (Page 147)

Mlodinow described an experiment in which people were asked to judge the length of lines. Researchers put several lines in a group A and others in a group B. Researchers found people thought lines that are in a group together are closer in length than they actually are and the difference in length between lines from different groups is different than it really is. Similar experiments with color differences and groups and guessing temperature changes in a thirty day period within one month or from the middle of a month to the middle of the next month is seen as more extreme. Same number of days but just saying it's a different month increases the estimate of change.

The implications are stunning. If people can be placed in categories and thought of as fundamentally defined by those categories we easily can misjudge people.

This reminds me of a terrible quote:

“The leader of genius must have the ability to make different opponents appear as if they belonged to one category. ” ―Adolf Hitler

That's a reminder of a terrible problem with human behavior and categorization.

Mlodinow wrote, "In all these examples, when we categorize, we polarize. Things that for one arbitrary reason or another are identified as belonging to the same category seem more similar to each other than they really are, while those in different categories seem more different than they really are. The unconscious mind transforms fuzzy differences and subtle nuances into clear-cut distinctions. Its goal is to erase irrelevant detail while maintaining information on what is important. When that's done successfully, we simplify our environment and make it easier and faster to navigate. When it's done inappropriately, we distort our perceptions, sometimes with results harmful to ourselves and others. That's especially true when our tendency to categorize affects our view of other humans--when we view the doctors in a given practice, the attorneys in a given law firm, the fans of a certain sports team, or the people in a given race or ethnic group as more alike than they really are." (Page 148)

Mlodinow wrote on how the term "stereotype" was created by French printer Firmin Didot in 1794. It was a printing process that created duplicate plates for printing. With these plates mass production via printing was possible.

It got its modern use by Walter Lippmann in his 1922 book Public Opinion. Lippmann is perhaps best known nowadays as a person frequently quoted by noted intellectual and American dissident Noam Chomsky. Chomsky has criticized the use of propaganda to manage populations by the government, wealthy individuals, corporations and media.

From Subliminal Mlodinow quoted Lippmann, "The real environment is altogether too big, too complex, and too fleeting for direct acquaintance...And although we have to act in that environment, we have to reconstruct it on a simpler model before we can manage with it." (Page 149) Lippmann called that model stereotype.

Lippmann in Mlodinow's estimation correctly recognized the source of stereotypes as cultural exposure. In his time newspapers, magazines and the new medium of film communicated in simplified characters and easily understood concepts for audiences. Lippmann noted stock characters were used to be easily understood and character actors were recruited to fill stereotypes.

Mlodinow described an experiment in which people were asked to judge the length of lines. Researchers put several lines in a group A and others in a group B. Researchers found people thought lines that are in a group together are closer in length than they actually are and the difference in length between lines from different groups is different than it really is. Similar experiments with color differences and groups and guessing temperature changes in a thirty day period within one month or from the middle of a month to the middle of the next month is seen as more extreme. Same number of days but just saying it's a different month increases the estimate of change.

The implications are stunning. If people can be placed in categories and thought of as fundamentally defined by those categories we easily can misjudge people.

This reminds me of a terrible quote:

“The leader of genius must have the ability to make different opponents appear as if they belonged to one category. ” ―Adolf Hitler

That's a reminder of a terrible problem with human behavior and categorization.

Mlodinow wrote, "In all these examples, when we categorize, we polarize. Things that for one arbitrary reason or another are identified as belonging to the same category seem more similar to each other than they really are, while those in different categories seem more different than they really are. The unconscious mind transforms fuzzy differences and subtle nuances into clear-cut distinctions. Its goal is to erase irrelevant detail while maintaining information on what is important. When that's done successfully, we simplify our environment and make it easier and faster to navigate. When it's done inappropriately, we distort our perceptions, sometimes with results harmful to ourselves and others. That's especially true when our tendency to categorize affects our view of other humans--when we view the doctors in a given practice, the attorneys in a given law firm, the fans of a certain sports team, or the people in a given race or ethnic group as more alike than they really are." (Page 148)

Mlodinow wrote on how the term "stereotype" was created by French printer Firmin Didot in 1794. It was a printing process that created duplicate plates for printing. With these plates mass production via printing was possible.

It got its modern use by Walter Lippmann in his 1922 book Public Opinion. Lippmann is perhaps best known nowadays as a person frequently quoted by noted intellectual and American dissident Noam Chomsky. Chomsky has criticized the use of propaganda to manage populations by the government, wealthy individuals, corporations and media.

From Subliminal Mlodinow quoted Lippmann, "The real environment is altogether too big, too complex, and too fleeting for direct acquaintance...And although we have to act in that environment, we have to reconstruct it on a simpler model before we can manage with it." (Page 149) Lippmann called that model stereotype.

Lippmann in Mlodinow's estimation correctly recognized the source of stereotypes as cultural exposure. In his time newspapers, magazines and the new medium of film communicated in simplified characters and easily understood concepts for audiences. Lippmann noted stock characters were used to be easily understood and character actors were recruited to fill stereotypes.

Mlodinow wrote, "In each of these cases our subliminal minds take incomplete data, use context or other cues to complete the picture, make educated guesses, and produce a result that is sometimes accurate, sometimes not, but always convincing. Our minds also fill in the blanks when we judge people, and a person's category membership is part of the data we use to do that." (Page 152)

Mlodinow described how psychologist Henri Tajfel was behind the realization that perceptual biases of categorization lie at the root of prejudice. Tajfel was behind the line length studies that support his hypothesis. Tajfel was a Polish Jew captured in France in World War II. He knew a Frenchman would be treated as an enemy by the Nazis while a French Jew would be treated as an animal and a Polish Jew would be killed.

He knew how he would be treated was entirely limited by the category he was placed in. Being a Polish Jew was a guarantee of death and so he impersonated a French Jew and was liberated in 1945. Mlodinow wrote, "According to the psychologist William Peter Robinson, today's theoretical understanding of those subjects "can almost without exception be traced back to Tajfel's theorizing and direct research intervention." (Page 153)

Mlodinow wrote, "The challenge is not how to stop categorizing but how to become aware of when we do it in ways that prevent us from being able to see individual people for who they really are." (Page 157) contrast this with

"At this point you’ve probably figured out that if your goal is to get someone to process new information and think critically about stereotypes (like [that] atheists are criminals or they should die) the absolute last thing we want is for them to feel threatened or attacked. The worst part about this is if you combine the process I just described with the sorts of negative emotional responses triggered by stereotypes and other biases, you can see that someone, if they’re all stressed by their perception of you…you’ve lost them, they’re not going to be able to listen. And you’ve additionally probably just given them a fun bad new memory to hang onto. " Nicole Currivan

Mlodinow wrote, "The stronger the threat to feeling good about yourself, it seems, the greater the tendency to view reality through a distortion lens."

(Page 197) compare to "First, as fun as some of you may think it is to attack and argue and ridicule people, just be aware that that will legitimately slam the door to rational understanding–of any point you have. And if you can’t call the discussion you’re having calm and rational, you are in serious danger of indulging your own emotional satisfaction to the point where you’re reinforcing someone’s distrust in all of us. And starting with the premise that someone needs to change or the inherent assumption that “I know more than you” will definitely create a strong stress response and pushback as well. Something we all inherently know but we do it anyway." Nicole Currivan

"Second, if you want to reduce stigma, it’s essential to reduce limbic system activation as much as possible whenever you’re talking to somebody. Any kind of threat, real or perceived, in the current moment or even just something they remember, something bad that they remember about the stigma that’s on the person they’re talking with, can shut down their ability to take in new information. And shuts down possibility for change. " Nicole Currivan

"As the psychologist Jonathan Haidt put it, there are two ways to get at the truth: the way of the scientist and the way of the lawyer. Scientists gather evidence, look for regularities, form theories explaining their observations, and test them. Attorneys begin with a conclusion they want to convince others of and then seek evidence that supports it, while also attempting to discredit evidence that doesn't. The human mind is designed to be both a scientist and an attorney, both a conscious seeker of objective truth and an unconscious, impassioned advocate for what we want to believe. Together these approaches vie to create our worldview." (Page 200)

Mlodinow went on, "As it turns out, the brain is a decent scientist but an absolutely outstanding lawyer. The result is that in the struggle to fashion a coherent, convincing view of ourselves and the rest of the world, it is the impassioned advocate that usually wins over the truth seeker." (Page 201)

Mlodinow described how we combine parts of perception and filling in blanks with self approving illusions. We give ourselves the benefit of the doubt unconsciously and do it over and over in hundreds of tiny ways without conscious awareness. Then, our conscious mind innocently looks at the distorted final product and sees a seemingly perfect, consistent and logical representation of reality as memories with no clue it's not anything but a pure recording of the past.

Mlodinow described how psychologists call this kind of thought "motivated reasoning." He explained how the way we easily get this is due to ambiguity. Lots of things that we sense aren't perfectly and absolutely clear. We can acknowledge some degree of reality but somewhat reasonably see unclear things in ways that give ourselves every benefit of the doubt. We can do it for allies, particularly in comparison to our enemies. We can see in-group members as good, if it's unclear and out-group members as bad if it's unclear. We can set standards extremely high to accept negative evidence against ourselves and our groups or set standards extremely low to accept negative evidence against out-groups. We can act reasonable about it, but really are using how we feel about beliefs to determine our acceptance of those beliefs, substituting comfort with acceptance for proof being established.

Mlodinow described how ambiguity helps us to understand stereotypes for people we don't know well and be overly positive in looking at ourselves. He described studies and experiments that strongly support the idea we are incorporating bias in our decisions unknowingly.

Crucially Mlodinow added, "Because motivated reasoning is unconscious, people's claims that they are unaffected by bias or self-interest can be sincere, even as they make decisions that are in reality self-serving." (Page 205)

Mlodinow described how recent brain scans show our emotions are tied up in motivated reasoning. The parts of the brain that are active in emotional decisions are used when motivated reasoning occurs, and we can't in any easy way divorce ourselves from that human nature.

Numerous studies have shown we set impossibly high standards to disconfirm our beliefs, particularly deeply held emotional beliefs like religious and political beliefs. We set impossibly low standards for evidence to confirm our beliefs.

We also find fallacies or weaknesses in arguments, claims and sources of information we disagree with while dropping those standards if the information supports our positions. It's so natural we often don't see it in ourselves but sharply see it in people with opposite beliefs. They look biased and frankly dimwitted. But they aren't alone in this.

We see ourselves as being rational and forming conclusions based on patterns of evidence and sound reason, like scientists but really have more lawyer in us as we start with conclusions that favor us and our current beliefs, feelings, attitudes and behaviors and work to find a rational and coherent story to support it.

Mlodinow ended his book, "We choose the facts that we want to believe. We also choose our friends, lovers, and spouses not just because of the way we perceive them but because of the way they perceive us. Unlike phenomena in physics, in life, events can often obey one theory or another, and what actually happens can depend largely upon which theory we choose to believe. It is a gift of the human mind to be extraordinarily open to accepting the theory of ourselves that pushes us in the direction of survival, and even happiness." (Page 218) end quote

So, between our prejudices, unseen biases and tendency to shut down critical thinking is there any hope ? Crazy as it sounds, we might actually want to have interactions with other human beings that are more than insults and close minded exchanges of motivated reasoning.

So, a guideline as to what to stick with or try to follow to stay on topic or on point is useful. If several people read it, understand it, understand that using tactics that trigger being more emotional often impair good judgement, impair the ability to to see individual people and situations and circumstances as they are with many subtle differences and unique details, and impairs even the ability to receive information and remember it accurately.

If behavior that cults like Scientology encourage that lowers the level of thinking can be identified and avoided thus making debates and discussions more rational wouldn't that be a good thing ?

Now I personally think that name-calling, ad hominem attacks, tu quoque (meeting criticism with criticism), the genetic fallacy (addressing the genesis or source of a claim rather than the claim), appeal to authority (treating a source as so infallible that a claim they support is treated as proven by their support without examination), glittering generalities or hasty generalities or red herring fallacies should be discouraged.

As none of us are perfect they will pop up. When one does if someone tells me I SHOULD pause and consider the claim that I have used a fallacy. Sometimes I will recognize that and can restate a claim or withdraw it. This doesn't mean a claim by the other person "wins" or is proven true. Thinking your claim is proven by the use of a fallacy in a claim in opposition to yours is the fallacy fallacy. I didn't make that up.

If I say "the earth is flat" and you say "only an idiot would say that", you just used a fallacy in your claim but it is irrelevant to mine. By the way I believe in a roughly globe shaped earth. So, we can acknowledge the presence of a fallacy in a claim and not treat it as life threatening or world shattering. Just because someone uses a fallacy in a claim doesn't mean their overall concept is wrong, sometimes it is and sometimes it isn't. Additionally, sometimes a person will claim a fallacy is being used when it is not. You can point this out.

I have many times posted articles critical of Scientology, for example, and got insults in response. I have asked that the person address my claims and not use ad hominem attacks many times in response. Curiously, many times the people defending Scientology often tell me I am using ad hominem attacks and they are not. The great thing about the internet is you can re-read comments and SEE what is there.

Often I post something saying Scientology is a harmful fraud, for example. Someone responds "only an idiot who never actually did anything in Scientology would ever say that because they lack the spiritual awareness to even comprehend Scientology." Okay.

I respond by telling them I was in Scientology for twenty five years, so their claim is false. They respond "then you must have not REALLY done Scientology ! Because it ALWAYS works when done properly !"

So , they are saying "if Scientology gets the results you want it is genuine but if it fails it is something else", but they have married their claims to unproven assumptions about me. Those are what is helping to turn down and hold do their critical thinking. And that is the barrier to beneficial communication.

You can call me any insult you can think up, and people certainly have. Go ahead, knock yourself out. It doesn't make them true. Not even a little bit. It also doesn't leave you in great shape for thinking.

Scientology gets people to think and feel in extremes. Extreme hate, extreme arrogance, extreme condescension, extreme disgust. These are not useful for critical thinking.

For a Scientologist or Independent Scientologist who chooses to engage with people who criticize Scientology I have a question - why can't you respond to criticism without using fallacies ? And the mind reading of "knowing my thoughts and motives and beliefs" without evidence is a fallacy. Scientology encourages people to think that critics have certain beliefs and motives and feelings but without good evidence deciding that a critic or person who disagrees with you thinks or feels something is making an unfalsifiable claim. It cannot be tested, it cannot be proven or disproven. It is a red herring and waste of time. If you believe it then it is a way to accept stereotypes and see people who disagree as broad categories and to reduce your own critical thinking. It may be emotionally comforting but it is terrible for critical thinking. You shouldn't rely on an assumption of knowing what someone else thinks. It's just not good logic.

We all do it. Human nature includes estimating the beliefs, feelings and behavior of other people. A large part of our thinking is devoted to it. But it is not a scientific approach, it is instinctive, largely unconscious, influenced by biases and highly inaccurate. So it is best set aside for careful examination of ideas in discussion. Just because I guess you think such and such is irrelevant to our conversation, unless that is the actual topic.

I dug up all this stuff for Scientologists who are going to keep on defending Scientology and resorting to the fallacy laden tactics Ron Hubbard required in Scientology doctrine. Everyone who was in Scientology for a long time and is familiar with a few dozen fallacies can see that Hubbard required them and frequently used them himself. Scientology is packed with generalities both glittering and hasty, appeal to authority regarding Hubbard, the genetic fallacy regarding critics and on and on. Scientology is set up to get you to think in those fallacies so you can never escape it.

And by getting members to become so emotional when criticism is detected, or even possible, it is intended to make any evidence against Scientology irrelevant because there is no critical thinking engaged to receive let alone examine it. Thousands and thousands of people have collected good arguments and evidence against Scientology to present to loved ones in Scientology only for it to prove worthless because they had no receptive audience to talk to.

Remember motivated reasoning is largely unconscious. We don't know when we are doing it. We can know we are more likely to do it if we get in a mode of using personal attacks and other fallacies. We can try to discipline ourselves to avoid insults, deciding the feelings and thoughts of people, using stereotypes and getting sidetracked in conversation. If a person starts with a central point then we can try to stick with that, not pivot off based on out feelings. If someone brings up criticism of someone or something I like or support for example feeling uncomfortable then solving that by pivoting to criticism of them or something or someone else is poor critical thinking. If I say for example that Ron Hubbard was convicted of fraud in France and you say a different court case with different people decades later was overturned that is completely irrelevant and we should both know it.

Everyone is free to behave however they choose. Plenty of people are going to insult you if you say much at all. Plenty will make up their unwarranted conclusions about your behavior, thoughts and feelings. That is life. It doesn't mean they are right. If they say it over and over and write it over and over it doesn't make it true.

If you want to have the opportunities to use your most logical, most rational thinking I recommend you remember that what they are doing is lowering their own rationality. They are diminishing their own thought. I can't pretend anyone can magically transform into a Vulcan like Spock and instantly become a perfectly logical being. That is not the point at all.

The point is we all can try to consider these ideas and if we believe it is likely true that resorting to personal attacks and similar measures reduces or shuts down critical thinking then we can strive to identify in ourselves when we do them and try to reduce it.

One last thing about critical thinking. Occasionally I see someone attack myself or Chris Shelton because we recommend critical thinking and write about it. It is not a magical transformation or religious practice. It is an approach to thinking in which you seek to improve the quality of your thinking. That is it. It doesn't mean you have achieved an enlightened state or higher awareness. It is just making an effort to fuck up less regarding thinking. So, if you can find any errors or flaws in the thinking, beliefs or conduct of someone who encourages critical thinking and you think " Aha ! I caught you ! You are not perfect ! So I can criticize you any way I want because you are a liar and a hypocrite !" You have missed the whole point of critical thinking. It is recognizing our flawed nature and trying to succeed despite it, not pretending to have overcome it.

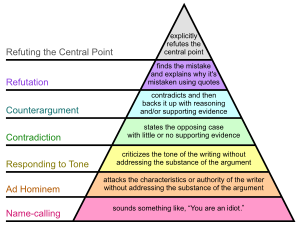

Hierarchy of disagreement

| Part of the series on Logic and rhetoric |

| Key articles |

| General logic |

| Bad logic |

The hierarchy of disagreement is a concept proposed by computer scientist Paul Graham in his 2008 essay How to Disagree.[1]

in his 2008 essay How to Disagree.[1]

Graham's hierarchy has seven levels, from name calling to "Refuting the central point". According to Graham, most disagreements come on one of seven levels:

to "Refuting the central point". According to Graham, most disagreements come on one of seven levels:

- 1: Refuting the central point (explicitly refutes the central point).

- 2: Refutation (finds the mistake and explains why it's mistaken using quotes).

- 3: Counterargument (contradicts and then backs it up with reasoning and/or supporting evidence).

- 4: Contradiction (states the opposing case with little or no supporting evidence).

- 5: Responding to tone (criticizes the tone of the writing without addressing the substance of the argument.)

- 6: Ad Hominem (attacks the characteristics or authority of the writer without addressing the substance of the argument).

- 7: Name-calling (sounds something like, "You are an idiot.").

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.